Muhammad Deckri Algamar, S.H., LL.M (Cand), Prof. Abu Bakar Munir

IE University Madrid (deckrialgamar@student.ie.edu),

DPEX Asia Sdn Bhd & Asosiasi Profesional Privasi Data Indonesia (abmunir@um.edu.my)

1. Background

In 19 January 2026, the Indonesian Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi) rendered judgment in Case No. 137/PUU-XXIII/2025 addressing Article 56 of Law No. 27 Year 2022 on Personal Data Protection (UU PDP) governing international data transfers. The petitioner challenged the law’s framework for transferring personal data outside Indonesia, arguing that such transfers implicate state sovereignty and require parliamentary authorization.

The petitioner’s broader concern was that personal data protection cannot be divorced from national sovereignty in the age of artificial intelligence. He framed data as the “new oil” driving AI development and national power, arguing that the U.S.–Indonesia trade framework created a risk of Indonesia becoming a data-extraction economy, potentially feeding AI development benefiting foreign powers while exposing Indonesian citizens to surveillance and manipulation risks.

The Constitutional Court rejected the petitioner’s arguments in full and upheld Article 56’s three-layer mechanism: (i) adequacy decisions, (ii) appropriate safeguards, and (iii) individual consent. The Court held that this framework remains consistent with Indonesia’s constitutional commitments to personal protection and data sovereignty.

2. Case Chronology

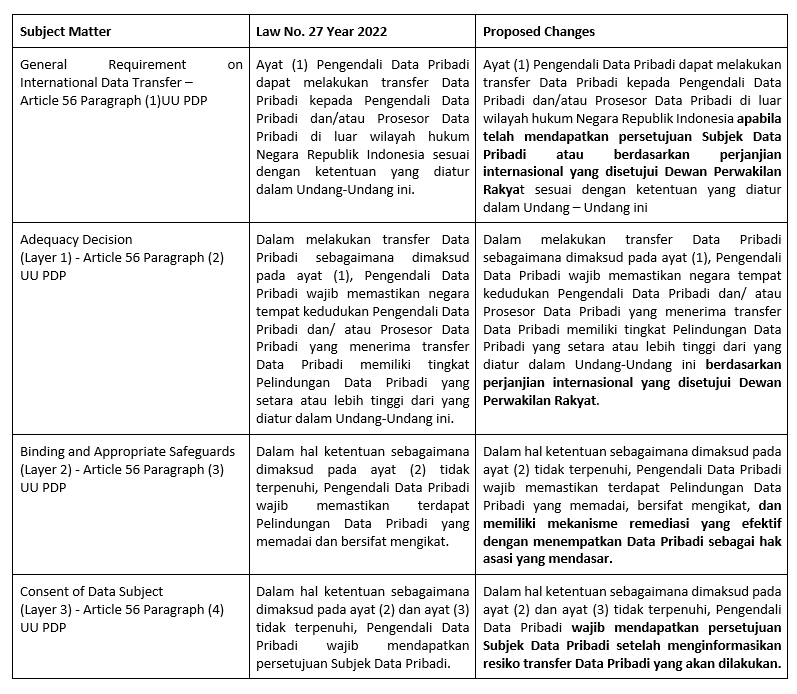

The petition was filed in 2025, coinciding with the White House and Indonesia’s preliminary announcement of a Framework for Negotiating a Reciprocal Trade Agreement with the United States. Indonesia committed to “provide certainty regarding the ability to transfer personal data out of its territory to the United States.” The petitioner’s main argument is that any trade agreements facilitating blanket data transfers must require House of Representatives approval. The following Table 1 represents the request of the petitioner:

Table 1: Petitioner’s Challenge to Article 56

3. Layer 1 (Adequacy Decision)

Petitioner’s Argument:

The petitioner argued that consent operates at two levels: general consent (broad regulatory approval) and particular consent (individual authorization). When personal data obtained without individual consent under law such as population registry data is transferred across borders, there must be both a general consent mechanism representing people’s collective will and particular consent from affected individuals.

The petitioner contended that Article 56’s UU PDP delegation of adequacy decision to individual data controllers and processors lacks clarity about who bears responsibility for assessing whether another country’s protections are truly equivalent. More fundamentally, the petitioner argued that cross-border data transfer agreements, particularly with major partners like the United States, constitute “international agreements producing broad and fundamental consequences for public life“. Hence, any adequacy decision should therefore require legislative approval by the House of Representatives, not merely administrative or executive action.

Government’s Response:

The Government responded by pointing to Articles 59 and 60 of the UU PDP, which mandate establishment of a Personal Data Protection Authority (Lembaga Pelindungan Data Pribadi). This body, not individual controllers, bears responsibility for assessing adequacy standards, developing cooperation frameworks with foreign regulators, and maintaining a list of adequate countries. However, as part of accountability principle – data controller and data processor is still required to carry out Transfer Impact Assessments.

Regarding the U.S.–Indonesia trade statement, the Government argued that “Indonesia will provide certainty regarding the ability to transfer personal data out of its territory to the United States” should not be read as an unconditional obligation to permit all transfers. Rather, it is a commitment to regulatory clarity and legal certainty within the UU PDP’s own framework.

Constitutional Court Decision

The Court accepted the Government’s position. On the institutional question, the Court confirmed that Articles 59–60 UU PDP vested the Personal Data Protection Authority as the entity with powers to determine adequacy decision, not the House of Representatives. Affirming that adequacy decision is the product of an executive function, not a legislative one.

On international agreements, the Court distinguished between “perjanjian internasional” (formal treaties affecting domestic law substance or incurring fiscal obligations) and routine regulatory cooperation (that of science, technology, engineering, trade, culture, shipment, double taxation prevention, and investment protection cooperation, or ratification with technical nature). Where the former requires ratification through the House of Representatives as per Article 10 of Law No. 24 Year 2000 on International Treaties, and the latter might not require it as per Article 11(1) of the Law. While major data-sharing frameworks might in some circumstances implicate Article 10 on Law of International Treaties, the Court declined to automatize all adequacy decision into that category. The Court reaffirmed that the Personal Data Protection Authority’s mandate under Articles 59–60 UU PDP already provides an institutional framework for managing such determinations.

DPEX & Asosiasi Profesional Privasi Data Indonesia Observation:

The Court did not clarify whether a bilateral data-sharing agreement between Indonesia and a foreign partner (such as the U.S.–Indonesia framework) would be classified as an “adequacy decision” under Article 56(2) UU PDP or as part of “appropriate safeguards” under Article 56(3) UU PDP.This ambiguity creates a risk that future U.S.–Indonesia data arrangements could be interpreted differently by different agencies.

Additionally, while the Court confirmed the Personal Data Protection Authority (PDP Authority), it did not specify what criteria and processes the Agency will use to make adequate determinations. The UU PDP and existing guidance contain broad, generic standards lacking operational clarity. Critically unanswered is whether challenges to adequacy decisions will be reviewed by the PDP Authority itself, the House of Representatives, or through the State’s Administrative Court (as Adequacy Decision being considered as a product of executive powers).

4. Layer 2 (Binding & Appropriate Safeguards)

Petitioner’s Argument:

The petitioner sought to strengthen Article 56(3) UU PDP by arguing that “appropriate safeguards” must include not only binding and enforceable terms, but also a substantive guarantee that data subjects retain effective legal remedies and enforceable rights when safeguards fail. The petitioner asked the Court to declare Article 56(3) UU PDP conditionally unconstitutional unless interpreted to require “enforceable data subject rights and effective legal remedies for data subjects.”

The petitioner contended that Article 56(3)’s of UU PDP that current language of “adequate and binding safeguards” remains vague about whether binding safeguards must actually translate into enforceable rights for Indonesian data subjects to challenge violations or seek remedies. A safeguard might be contractually binding but still lack an operative mechanism for data subjects to enforce their rights, particularly if the receiving country’s legal system lacks an ombudsperson, independent review body, or accessible court remedies. This concern echoes the European Court of Justice’s reasoning in Schrems II (Case C-311/18), where the CJEU found that mere contractual safeguards were insufficient if data subjects could not pursue effective remedies.

Government’s Response:

The Government defended the existing language of Article 56(3) UU PDP as workable and appropriately flexible. They argued that “adequate and binding safeguards” already consider protective instruments such as Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), binding corporate rules (BCRs), and contract terms imposing enforceable obligations. In essence, their position is that existing Article 56(3) UU PDP already encapsulates what the petitioner had requested.

Constitutional Court Decision:

The Court upheld the Government’s position, declining to insert “enforceable data subject rights and effective legal remedies” as a mandatory textual addition to Article 56(3) UU PDP.

DPEX & Asosiasi Profesional Privasi Data Indonesia Observation:

While debates of Layer 2 do not go very deep, it shows that both petitioner and the Government agrees that “Appropriate and Binding Safeguards” must be enforceable. Going forward, it remains important for the PDP Authority to detail down the technical requirements of developing Layer 2 mechanism through Binding Corporate Rules (BCR) or Standard Contractual Clauses (SCC) similar to how the European Data Protection Board establishes clarity on utilizing each mechanism. It must also be considered on how the PDP Authority will assess existing BCR/SCC worldwide that has been used by multiple entities in Indonesia, where the BCR/SCC have already been approved by the European Data Protection Board or ASEAN frameworks. In addition to this, the Court did not respond to the Government’s contention that Transfer Impact Assessments must be carried out to all data transfer activities (p. 135) as the implementation of accountability principle. This silence must be clarified as it would defeat the purpose of having layered mechanisms in data transfers. In several jurisdictions such as Singapore, Thailand, and European Union which is further clarified within (CNIL Guideline on Transfer Impact Assessment), when transfers is based upon Adequacy Decision (Layer 1) or Consent (Layer 3, as specific derogations), there is no need for a controller or processor to conduct Transfer Impact Assessment.

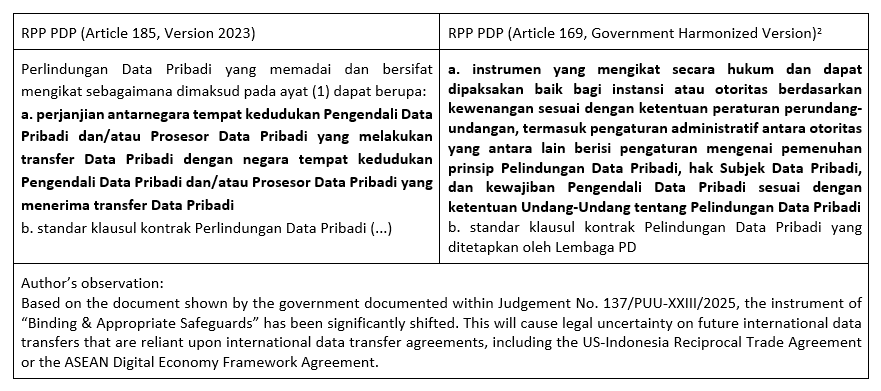

One notable point that was missing from the discussion is the positioning on whether International Agreements (one such as EU-US Data Privacy Framework) will be considered within Layer 1 (Adequacy) or Layer 2 (Binding and Appropriate Safeguards). Authors note that under the Draft Implementing Regulation of Law No. 27 Year 2022 on Personal Data Protection (RPP PDP, Version 2023), international agreements are explicitly positioned within Layer 2. Court’s and both parties’ omission in referencing this document may create legal uncertainty in the future. This ambiguity risks inconsistent interpretation by different agencies, undermining regulatory certainty.

Table 2: International Agreement as Binding & Appropriate Safeguard

1Copied from excerpt of Judgement Decision No. 137/PUU-XXIII/2025

5. Layer 3 (Data Subject Consent)

Petitioner’s Argument:

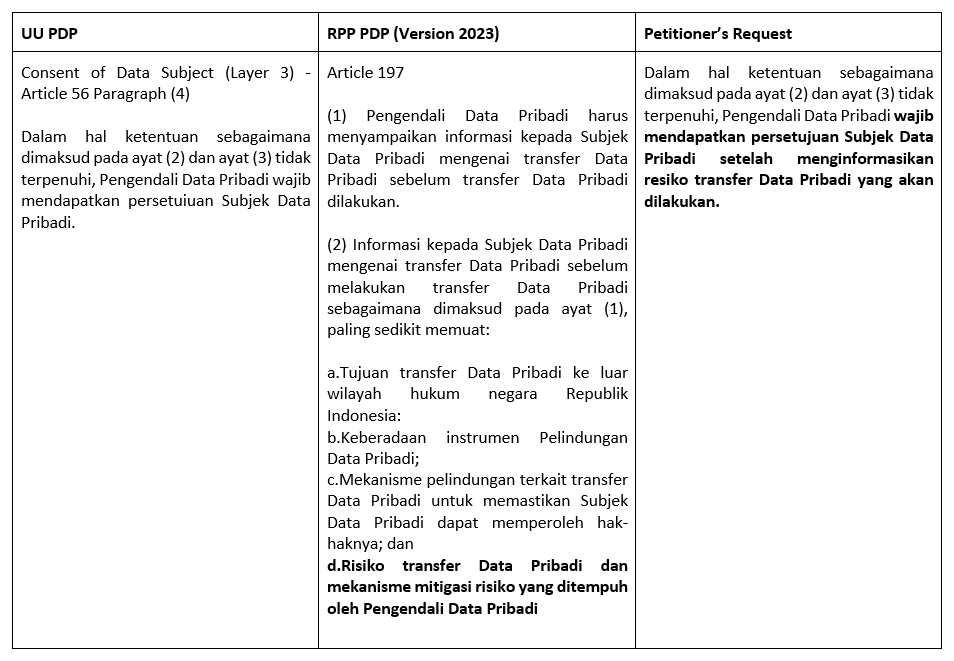

For Article 56(4) UU PDP, which permits transfer based on individual data subject consent when adequacy and safeguards are absent, the petitioner sought a conditional declaration of unconstitutionality requiring that consent be informed. Specifically, data subjects must be explicitly warned of the absence of adequacy and appropriate safeguards before agreeing to transfer. The petitioner drew on EU GDPR Article 49(1)(a), which explicitly requires that consent be given “after having been informed of the possible risks of such transfers for the data subject due to the absence of an adequacy decision and appropriate safeguards.”

Government’s Response:

The Government strongly resisted changing the existing process where individual consent can act as a basis for transfers to non-adequate jurisdictions. Under Article 56(4) UU PDP, data subjects retain the ability to authorize transfer even absent adequacy or safeguards, a residual protection reflecting the principle that individuals should not be wholly stripped of agency over their own data. The Government warned that eliminating or severely restricting consent would be inconsistent with global practice. The Government also referred to the concept of “explicit and informed consent” found under UU PDP where any consent being used must meet a certain set of requirements, which already addressed the potential risks of data transfer.

Constitutional Court Decision:

The Court sided with the Government. Court reasoned that consent remains a legitimate and necessary mechanism because it preserves individual agency and reflects the reality that data subjects may wish to benefit from services offered by foreign entities even if those countries lack formal adequacy decision. The Court also cited Article 20 of UU PDP, reasoning that consent received as a legal basis for personal data processing is already considered “informed” consent, as the PDP Law sets out requirements for what constitutes explicit consent. The Court concluded there was no reason to impose an additional layer of risk disclosure specific to cross-border transfers.

DPEX & Asosiasi Profesional Privasi Data Indonesia Observation:

While the Court’s and Government’s reasoning are sound, it has failed to distinguish the concept of Consent as legal basis of personal data processing with Consent as a basis for international data transfer. The Court’s reasoning presupposes that initial consent comprehensively covers all future transfers, but this conflicts with best practices requiring specific, informed authorization for each new international transfer.

In EU GDPR, consent for transfer is distinct from consent to process data. Under GDPR Article 49(1)(a), consent for transfer to a third country may take place only if the transfer is not repetitive, concerns only a limited number of data subjects, is necessary for compelling legitimate interests, and the controller has assessed all circumstances and provided suitable safeguards. Indonesia’s Court did not import this distinction, leaving ambiguity about whether blanket initial consent can cover multiple transfers over time.

One interesting note is that the Government argued against the petitioner’s request while the RPP PDP already accommodated such a request. The omission of Government from declaring the argument is interesting while also indicating that the Government may have erred in understanding the distinction between the two types of Consent.

Table 3: Consent as Basis for Transfer under UU PDP, RPP PDP, and Petitioner’s Request

6. Conclusion

The Constitutional Court’s judgment affirms Indonesia’s adoption of a three-layer, best-practice approach to cross-border data transfers while also dispelling initial fear of blanket cross-border data transfer agreements. By rejecting the petitioner’s demand for parliamentary approval of every adequacy decision, the Court preserved regulatory flexibility for the PDP Authority while maintaining constitutional safeguards for individual data subjects.

However, the decision’s practical utility depends on the PDP Authority’s performance. Until the PDP Authority issues clear adequacy decision, operational criteria, and implementing guidance, organizations will face uncertainty regarding which transfers require safeguards, which require consent, and what form those safeguards and consents must take. Organizations should remain engaged with the PDP Authority forthcoming regulations and maintain data governance practices that exceed minimum legal requirements, particularly for sensitive personal data and high-risk jurisdictions.

1 This analysis is based on Constitutional Court Decision No. 137/PUU-XXIII/2025 (rendered 19 January 2026) and represents the authors’ interpretation of the judgment and its implications for Indonesian data protection law. This document is provided for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

© 2026 Abu Bakar Munir and Muhammad Deckri Algamar. All rights reserved.